Tokenization, Decoding and Sampling Strategies for Language Models

Tokenization

The process of generating text from an initial input involves tokenizing the text into numbers since models cannot process raw text. Tokenization converts sequences of text into numerical data and is an essential step in natural language processing (NLP).

One simple tokenization method is to break the text into individual characters, assigning each a unique numerical ID. This works well for languages like Chinese but is less efficient for languages like English. It results in a large number of tokens for even small strings, making it harder for models to capture the meaning and structure of the text. Each character carries little information, reducing accuracy and performance.

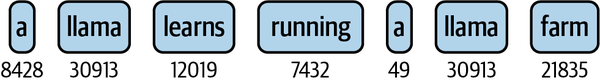

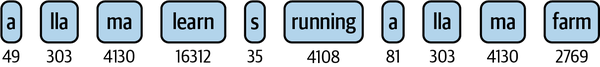

Another method is word-level tokenization, where entire words are assigned unique IDs. While this captures more meaning, it has its own challenges, such as handling unknown words (e.g., typos or slang), word variations (e.g., “run,” “runs,” “running”), and managing a large vocabulary that can exceed half a million words in languages like English.

Modern tokenization strategies combine the benefits of both approaches by splitting text into subwords. This allows models to efficiently capture the structure and meaning while handling unknown words and word variations. Common word parts are grouped together into a single token, while complex words or inflected forms are split into meaningful subword units.

Decoding

Text generation can be done using different strategies. One simple method is greedy decoding, where the model picks the most likely next word at each step. However, this can result in suboptimal sequences because it ignores the overall sentence probability. For example, it might choose “Sky blue” over a more coherent “Sky rockets soar”.

A better approach is beam search, which explores multiple candidate sequences and keeps the most likely ones. This results in more coherent outputs but is slower and can still be repetitive.

To reduce repetition, we can use settings like:

🔹 repetition_penalty: discourages repeated words.

🔹 bad_words_ids: blocks unwanted words.

Beam search works well for tasks with predictable output length (e.g., translation or summarization), but not as well for open-ended generation.

Interestingly, human language is less predictable than model-generated text. To better mimic human unpredictability, researchers propose a method called nucleus sampling, which avoids only selecting high-probability words.

Sampling

Sampling strategies control how tokens (words or subwords) are selected during text generation. Different strategies trade off between creativity, diversity, and coherence. Here’s an overview of the main types of sampling strategies used in LLMs:

🔹 Top-k Sampling (k-sampling)

What it does: From the top k most probable tokens, samples one randomly.

Pros: Adds diversity and avoids low-probability “junk”.

Cons: Still rigid; may ignore useful tokens just outside the top-k.

Hyperparameter: k (typical values: 10–100).

Use case: Creative writing, chatbots.

🔹 Top-p Sampling (Nucleus Sampling)

What it does: Chooses from the smallest set of tokens whose cumulative probability exceeds p.

Pros: More dynamic and adaptive than top-k.

Cons: Slightly harder to control.

Hyperparameter: p (typical values: 0.8–0.95).

Use case: Dialogue, story generation, open-ended text.

🔹 Temperature Sampling

What it does: Controls randomness in sampling by scaling the logits before softmax.

Low temperature (<1.0) → more deterministic.

High temperature (>1.0) → more random and creative.

Usually used with: Top-k or top-p sampling.

Use case: Fine-tuning creativity levels in generation.

🔹 Typical Sampling

What it does: Samples tokens that have typical (i.e., average) information content, avoiding overly common or rare tokens.

Pros: Avoids degenerate repetition while keeping coherence.

Use case: Balanced generation; newer and increasingly popular.

🔹 Contrastive Search (Decoding)

What it does: Combines greedy search with diversity-promoting objectives using contrastive scoring.

Pros: High coherence and fluency, especially for long-form text.

Cons: More complex and computationally expensive.

Use case: Applications needing coherent long outputs (e.g., essays, articles).

🔹 Random Sampling (Unconstrained)

What it does: Samples from the full probability distribution.

Pros: Maximum randomness.

Cons: Very prone to generating incoherent or irrelevant text.

Use case: Rarely used on its own; mostly for testing or exploration.